Circuit Assignments/A Death Penalty Case

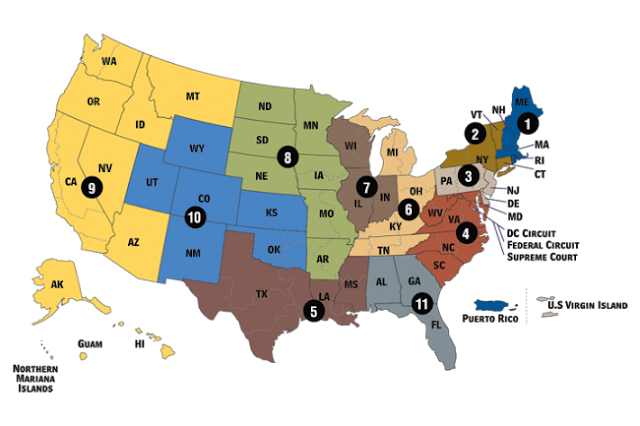

Map of the Federal Appellate Courts

Did you know that the 13 federal circuit courts (11 numbered circuits plus the District of Columbia and the Federal Circuit) each get their own Justice? They do. And they have for a long time. Effective June 27, 2017 (basically at the end of the October 2017 term) the current circuit assignments were issued. Other than being required by statute (28 U.S.C. §42), why is this done?

As our friends at SCOTUSblog succinctly put it:

"Circuit Justices are responsible for ruling on certain motions arising from their assigned circuits, such as motions for extensions of time. In the case motions for a stay of execution or other motions relating to death penalty matters, the Circuit Justice ordinarily refers the motion to the Court as a whole, but takes the lead in recommending a disposition of the motion."

Justices are quite often assigned a circuit that has some relevance to their background. For example, Justice Breyer is assigned the First Circuit, the appeals court on which he served before he was a Supreme Court justice. The same goes for Justice Alito, assigned the Third Circuit where he too was a judge. This is not always the case. Justice Gorsuch was not assigned to the Tenth Circuit, though he served there, instead, he was assigned to the Eighth Circuit. Justice Thomas, though not serving on the Eleventh Circuit, was assigned to that court of appeals. (He was born in Savannah, Georgia, though).

Besides extensions of time, this circuit-specific task also applies to things like stays in civil matters, injunctions, and generally what might be called housekeeping matters. Very different from the days after the Revolution when the justices literally had to "ride circuit" because there were no circuit judges. A great short article on the history of this practice can be found here.

Normally fairly mundane stuff. Until it isn't.

[Note: I would especially recommend clicking on the links below. Seeing death penalty appeals in print has a power that just reading about them does not. And this only gives you a glimpse into how convoluted it can be].

On January 24, 2018, Justice Thomas received this:

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 2017

______________________________________________________

VERNON MADISON, Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF ALABAMA, Respondent.

______________________________________________________

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE ALABAMA SUPREME COURT

______________________________________________________

APPLICATION FOR A STAY OF EXECUTION

______________________________________________________

THIS IS A CAPITAL CASE

WITH AN EXECUTION SCHEDULED

FOR THURSDAY, JANUARY 25, 2018

To the Honorable Clarence Thomas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and Circuit Justice for the Eleventh Circuit:

Tomorrow, January 25, 2018, the State of Alabama seeks for the second time to execute Vernon Madison, a 67-year-old man who has been on Alabama's death row for over 30 years...

The cover page of the actual cert petition, filed simultaneously, was even more clear:

CAPITAL CASE WITH AN EXECUTION

SCHEDULED FOR JANUARY 25, 2018

at 6:00 pm

______________________________________________________

Justice Thomas, because he is the Justice assigned to the Eleventh Circuit, which includes Alabama, was the first Justice to see the application for the stay. All applications for stays of execution go in the first instance to the Circuit Justice. As is the norm, Justice Thomas referred the application to the whole Court, which also has the cert petition in front of it. Justice Thomas issued an order staying the execution "pending further order of the undersigned [Justice Thomas] or of the Court". After conferring, the Court issued an order on January 25 which stated:

"The application for stay of execution of sentence of death

presented to Justice Thomas and by him referred to the Court is

granted pending the disposition of the petition for a writ of

certiorari. Should the petition for a writ of certiorari be

denied, this stay shall terminate automatically. In the event

the petition for a writ of certiorari is granted, the stay shall

terminate upon the issuance of the mandate of this Court.

Justice Thomas, Justice Alito, and Justice Gorsuch would

deny the application".

Translation: (1) Madison's execution scheduled for January 25th is stayed; (2) if the Supreme Court denies cert, the stay automatically goes away; (3) if the Supreme Court grants certiorari (grants review) the execution is stayed until the Court renders an opinion (the "mandate"); (4) Justices Thomas (the first to see the application for stay of execution), Alito, and Gorsuch would deny the stay.

But it's not the first time Vernon Madison has brought his case before the Supreme Court. If you type "Madison v. Alabama" into the Supreme Court docket search, you will get six different docket numbers (6 different cases) for Madison v. Alabama, and two different docket numbers for the related cases of Dunn [the Commissioner of the Alabama Department of Corrections] v. Madison, for a total of eight in all.

It won't surprise you that eight separate cases are hard to summarize in a blog post; it takes five pages in the cert petition (essentially a quarter of the petition, which I recommend you read). I will only focus on this cert petition, although if you read the "Statement of the Case" on pages 2-7 you will get a complete history of Madison's fight to be spared execution.

There is one question presented in the petition:

Vernon Madison was sentenced to death by a circuit judge despite a jury verdict for life. In 2017, Alabama abolished the practice of judicial override. This case thus gives rise to the following question:

Now that the State of Alabama has abolished the practice of judicial override, does the execution of a prisoner who was sentenced to life by a jury render his execution arbitrary and capricious in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution?

Petition at i.

Although it might look like one question, there really are at least two:

(1) can a person be sentenced to death by the judge when the jury sentences that person to life without parole? When Madison was sentenced after his third trial (his first two convictions were overturned because the prosecution struck all African-Americans from the first jury and relied on facts not in evidence for their expert testimony in the second trial) judicial override was allowed but the Supreme Court held the practice unconstitutional in 2016 in Hurst v. Florida 136 S. Ct. 616 (2016). "In so holding, Hurst invalidated death penalty sentencing schemes, such as Alabama’s

superseded law, that allowed for judicial override of a jury’s sentencing verdict specifying life without parole". Petition at 21.

I'll just quote from one of the documents filed on Madison's behalf:

"Mr. Madison therefore moves this Court to stay his execution and grant his petition for certiorari to address the substantial question of whether executing Mr. Madison, whose severe cognitive dysfunction leaves him without memory of his commission of the

capital offense or ability to understand the circumstances of his scheduled execution, violates evolving standards of decency and the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. In support of this motion, Mr. Madison states as follows:

It is undisputed that Mr. Madison suffers from vascular dementia as a result of multiple serious strokes in the last two years and no longer has a memory of the commission of the crime for which he is to be executed. His mind and body are failing: he suffers from encephalomalacia (dead brain tissue), small vessel ischemia, speaks in a dysarthric or slurred manner, is legally blind, can no longer walk independently, and has urinary incontinence as a consequence of damage to his brain" Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Mobile County Circuit Court and Application for Stay of Execution, p. 2" [Yes, there were multiple applications for stay and cert petitions filed in this case due to Alabama law].

The Supreme Court is empowered to grant petitioner a stay of execution in order to adjudicate his constitutional claims. Barefoot v. Estelle, 463 U.S. 880 (1983) states that a stay may be granted when there is “a reasonable probability that four members of the Court would consider the underlying issue sufficiently meritorious for the grant of certiorari...a significant possibility of reversal of the lower court’s decision; and...a likelihood that irreparable harm will result if that decision is not stayed.” Further, a stay should be granted when necessary to “give non-frivolous claims on constitutional error the careful attention that they deserve” and when a court cannot “resolve the merits [of a claim] before the scheduled date of execution to permit due consideration of the merits.” Id. at 888-89 Application for Stay of Execution filed January 24, 2018 at 5.

One more important item. On November 6, 2017, the Court entered a per curiam (unsigned, "by the court") opinion in the related case of Dunn v. Madison. Although unanimously denying Madison's habeas corpus petition, and finding that the Alabama courts did not violate the rule stated in Panetti because while Madison did not remember the crime itself, he is aware that he murdered someone and that Alabama will put him to death for that crime, three members of the Court concurred only because of the demanding standards imposed by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 under which habeas will be granted only if the state trial court’s adjudication of his incompetence claim “was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by” this Court, or else was “based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented” in state court. 28 U. S. C. § 2254(d). This is why while mentioning Madison's dementia, the petition focuses on the judicial override issue.

Absent this statute, Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor may not have reversed the Eleventh Circuit that ruled in Madison's favor, and Breyer is known to be a harsh critic of the death penalty, at least in terms of how it is administered. Could these be three of the four votes Madison needs to grant his cert petition? We know at least three that aren't. That leaves Justices Kennedy, Kagan, and Chief Justice Roberts.

Only time will tell.

Comments

Post a Comment